Jordània, dia 7: visita a Amman i Jarash ( 3 de gener de 2018) (VII)

Els ammonites a la Bíblia

Segons el Gènesi, els ammonites són els descendents de Benammí (també conegut com a Ammí o Ammon), un dels fills de Lot, nebot d'Abraham, nascut d'una relació incestuosa amb la seva

pròpia filla petita. El Gènesi els considera parents propers dels israelites (descendents de Jacob), dels edomites (descendents d'Esaú) i encara més dels moabites (descendents de Moab). La tribu dels ammonites va exterminar els

zamzunminis (zuzim o zamzummim) i es va establir als seus territoris, al nord

de Moab i a l'est del riu

Jordà.

Segons l'Èxode, els israelites van trobar a la seva arribada a Canaan el Regne de Sihon com a dominador de Gilead, el país a l'est del riu

Jordà,

ja que aquest havia expulsat els ammonites del seu territori. L'exèrcit hebreu, comandat per Josuè, va demanar creuar el seu territori, però no

els hi fou permès; aleshores, foren exclosos

de la Congregació del senyor durant deu generacions i van veure com

els nouvinguts van ocupar les seves terres. Tres-cents anys després, un rei

ammonita va envair les terres d'Israel fins que fou derrotat pel jutge

d'Israel, Jeftè.

En temps del rei

David,

el rei ammonita Nahaix va pactar una aliança amb Israel. Però quan va morir, el fill i successor,

Hanum, va malfiar-se dels jueus i es va trencar l'acord. Aleshores, va

declarar la guerra a David i, juntament amb els siris, van atacar Israel. La guerra va durar prop d'un any, fins que

l'exèrcit israelita del general Joab va arrasar Rabà, la capital ammonita.”

Amb tot, entrem un moment al

museu. El guia ens conta que van descobrir 33 estàtues de diferent mida, fetes

de guix amb els ulls pintats de negre. Aquestes estàtues, però, s’havien de

coure a 900ºC i encara a dia d’avui es desconeix com entre el 6000 i 8000aC es

va aconseguir fer.

De fet, a Jericó, datada

d’aproximadament el 6000aC, també s’hi van trobar estàtues semblants.

Dins del museu hi ha restes de moltes èpoques, però

sobretot en destaca la joia de la corona que no és altre que les estàtues d’Ayn

Gazhal, que tal i com es conta a viquipèdia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%27Ain_Ghazal_Statues ):” A number of monumental lime plaster and reed statues dated to the Pre-pottery

Neolithic B period have been discovered in Jordan, at the site of Ayn Ghazal. A total of 15 statues and 15

busts were discovered in 1983 and 1985 in two underground caches, created about

200 years apart.

Dating to between the mid-7th

millennium BC and the mid-8th millennium BC,[ the statues are

among the earliest large-scale representations of the human form, and are

regarded to be one of the most remarkable specimens of prehistoric art from the

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period. They are kept in the Jordan Museum in Amman.

Description

The figures are of two types,

full statues and busts. Some of the busts are two-headed. Great effort was put into modelling the heads, with

wide-open eyes and bitumen-outlined irises. The statues represent men, women

and children; women are recognizable by features resembling breasts and

slightly enlarged bellies, but neither male nor female sexual characteristics

are emphasized, and none of the statues have genitals, the only part of the

statue fashioned with any amount of detail being the faces.

The statues were formed by

modelling moist plaster from limestone on a reed core using plants that grew

along the banks of the Zarqa River. The reed decayed over the millennia, leaving plaster

shells with a hollow interior. Lime plaster is formed by heating limestone to

temperatures between 600 and 900 degrees celsius; the product, hydrated lime is then combined with water to make a dough, which

was then modelled. Plaster becomes a water-resistant material when it dries and

hardens. Heads, torsos and legs were formed from separate bundles of reeds

which were then assembled and covered in plaster. The irises were outlined with

bitumen and the heads were covered with some sort of wig.

They are comparatively tall, but

not human-sized, the tallest statues having a height of close to 1 m. They

are disproportionately flat, about 10 cm in thickness. They were

nevertheless designed to stand up, probably anchored to the floor in enclosed

areas and intended to be seen only from the front. The way the statues were

made would not have permitted them to last long. And since they were buried in

pristine condition it is possible that they were never on display for any

extended period of time, but rather produced for the purpose of intentional

burial.

Discovery and conservation

The site of Ayn Ghazal was discovered in 1974 by

developers who were building a highway connecting Amman to the city of Zarqa. Excavation began in 1982. The

site was inhabited during ca. 7250–5000 BC. In its prime era, during the first

half of the 7th millennium BC, the settlement extended over 10–15 hectares

(25–37 ac) and was inhabited by ca. 3000 people.

The statues were discovered in

1983. While examining a cross section of earth in a path carved out by a

bulldozer, archaeologists came across the edge of a large pit 2.5 meters

(8 ft) under the surface containing plaster statues. Excavation led

by Gary O.

Rollefson took place in 1984/5, with a second set of

excavation under the direction of Rollefson and Zeidan Kafafi during 1993–1996.

A total of 15 statues and 15

busts were found in two caches, which were separated by nearly 200 years.

Because they were carefully deposited in pits dug into the floors of abandoned

houses, they are remarkably well-preserved.Remains of similar statues found

at Jericho and Nahal Hemarhave survived only in fragmentary state.

The pit where the statues were

found was carefully dug around, and the contents were placed in a wooden box

filled with polyurethane foam for protection during shipping. The statues

are made of plaster, which is fragile especially after being buried for so

long. The first set of statues discovered at the site was sent to the Royal

Archaeological Institute in Great Britain, while the second set, found a few

years later, were sent to the Smithsonian

Institution in New York for restoration work. The statues were

returned to Jordan after their conservation and can be seen in the Jordan Museum.

Part of the find was on loan in

the British Museum in 2013. One specimen was

still being restored in Britain as of 2012. ”

Dins del museu hi passaria molta estona contemplant tot

el que hi ha de totes les èpoques, però no tenim gaire temps. Em crida

l’atenció, però, alguns cranis als quals sembla que se’ls havia practicat

alguna mena de cirugia primitiva, i en alguns, més d’una vegada i tot.

Sortint, tenim temps de poder contemplar una petita part

del que queda d’una estàtua d’Hèrcules, que es creu que feia 13m d’alt i que és

una mà. Sembla que hi hagué un terratrèmol que va destruir-la... Allí també hi

havia un temple, el temple d’Hèrcules, construït entre el 162-166 aC. Sobre

aquest temple, del qual encara se’n conserven alguns vestigis, es conta el

següent (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_of_Hercules_(Amman) ):” Temple

of Hercules is a historic site in the Amman Citadel in Amman, Jordan. It was built in the same period

as the Roman

amphitheater below between (162-166) AD. It is thought to

be the most significant Roman structure in the Amman Citadel, according to an inscription the temple was built

when Geminius

Marcianus was governor of the Province of Arabia (AD

162-166).

The temple is about 30 meters

long by 24 meters wide and additional with an outer sanctum of 121 meters by 72

meters. The portico has 6 columns about 10 meters

tall. Archaeologists believe that since there are no remains of additional

columns the temple was probably not finished, and the marble used to build the

Byzantine Church nearby.

The site also contains a hand

carved out of stones resembling the hand of Hercules. The statue is

estimated to have been over 12 meters tall, and probably destroyed in an

earthquake. All that remains are three fingers and an elbow. ”

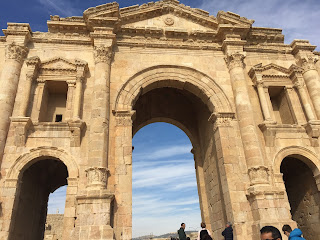

(Continuarà)(La fotografia és d'una de les portes d'entrada de Jarash)

Comentaris